Blogpost: She said, he said, they say: Constructing the linguistics of interdisciplinarity

Thinking about interdisciplinarity is usually accompanied by a feeling of excitement due to the novelty. Interdisciplinarity is in fact commonly interpreted as a magical word that will open the doors to the realm of diverse possibilities. What couldn’t we obtain by joining knowledge, forces and aims? What things could be accomplished and reached if only disciplines would work together? Interdisciplinarity acts thus as verb, synonymous to creation, ideation. It gives us the idea of jumping over our limits and creating beyond boundaries.

Coined as a term in the USA sometime between years 1925-30 during the Social Science Research Council’s six famous Hanover conferences and explicitly later mentioned by Louis Wirth’s report to the Council of 1937, the term responds to the ever-present need of answering enquiries that go beyond the boundaries of single disciplines . The term is contemporary, so to say, because up until the beginning of the XIX century knowledge could still be considered “systematic”. That is, disciplines were still part of a whole or unity, and much of the works of the most famous thinkers in our culture were the products of comprehensive research that does not differentiate into which we will now classify as humanistic and scientific disciplines1.

The term itself is not radical when considering the most common type of interdisciplinarity, that is, the dialog or interaction between close disciplines. Difficulties arise today when we think about overcoming the abyss between humanities and sciences, not as an exercise in flirtation but with the aim to create a specific curriculum designed to do so. The idea is not to try to go back in history and recover educational profiles and curricula that could produce a Newton, a Copernicus, a Kant, but to offer the instruments for students in the scientific and humanistic disciplines to interact with each other in a way that demonstrates to be proficuous both ways: to be able to “open the mind”, “step out of the comfort zone”, develop some skills that pertain to the other’s discipline and, mostly, to be able to understand the other’s language. Understanding is the basis for common and creative work. It is this last part that is the most crucial to develop when constructing a project such as ABRA; this can be interpreted as constructing the linguistics of interdisciplinarity.

ABRA is a consortium where academics coming from disciplines on opposites sides of the Higher Education spectrum interact. The consortium is composed by members that have shown previous interest or experience in each other’s disciplines. They already have concrete examples of what it means to successfully navigate over one’s discipline boundaries. Experiences vary though, and the interactions are multiple and diverse in nature. To construct a common language, the first step the consortium has taken was “to show” the others the meaning of each one’s words. What do every one of the participants mean when they talk about the subject, about sustainability, which objects do they manipulate, how does their work become real and under which forms?

To this aim, a series of seminars are currently in course where all the participants to the project are presenting their work. Despite what could be intuitively thought about sharing very specific and specialized work with professionals coming from other disciplines, the discussions taking place have demonstrated to be extremely fruitful. Not once has the seminar ended before its allotted time, with discussions and questions overrunning the dedicated time of these meetings. Praise, curiosity, clarifications and discussions follow the different participant’s intervention without fault. The result has been the evolution from these informal “talks” into dedicated meetings that have as a concrete aim, the discussion about the definition of specific terms. The awareness that the terms used to enlighten the different work and research mean different things for the diverse participants has led to a proper work of language interpretation and reinterpretation.

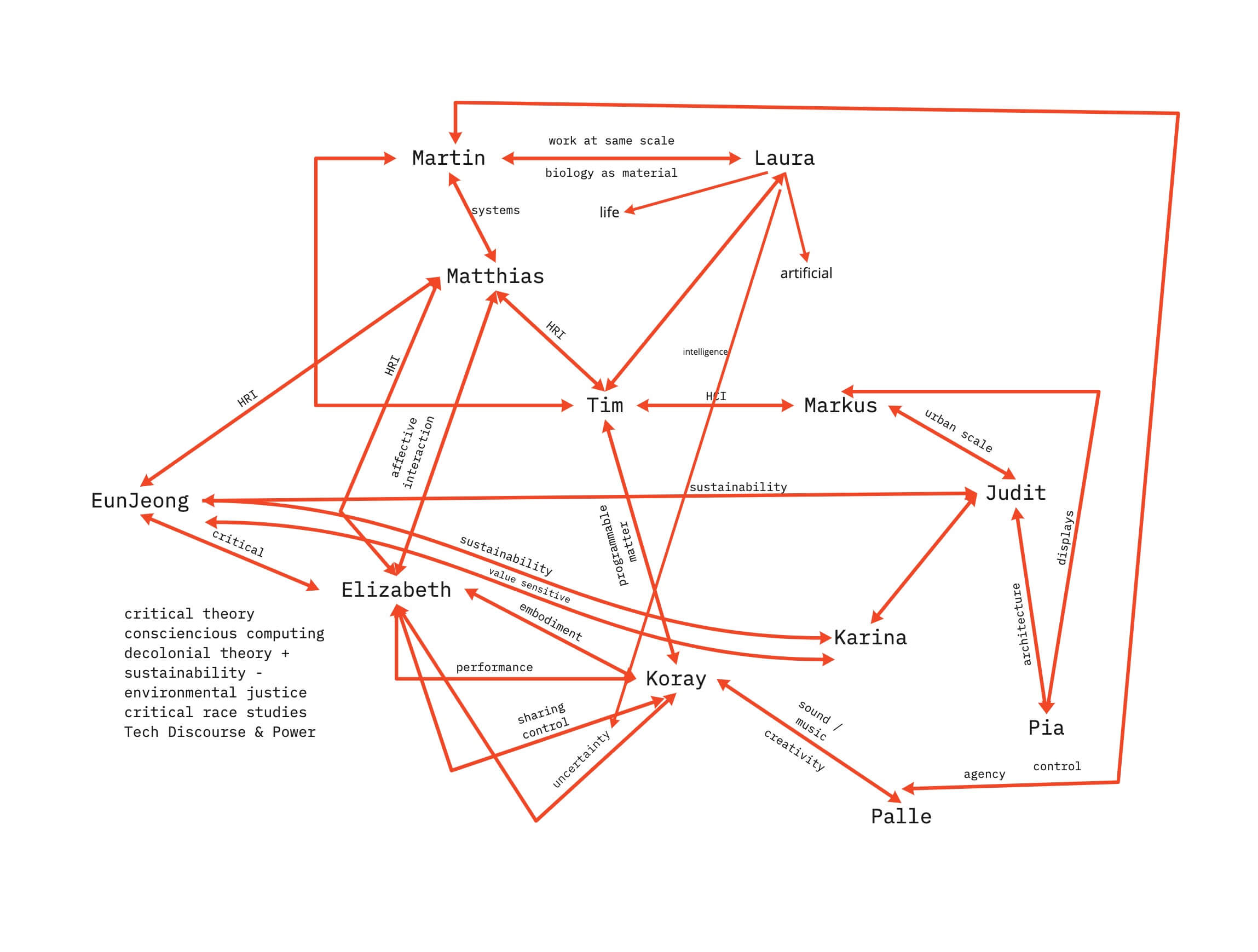

ABRA’s interdisciplinary conceptual map. The map links researchers and disciplines through concepts.

As a concrete example of this ongoing work, at present ABRA is discussing the term agency. As it is easy to imagine, this concept has different meanings and nuances in the different fields at work. The meaning is not the same with participants working with robots or music or biology or artificial cells. At this discussion, terminology is being put under question. For example, how do perception or intention influence our understanding of agency? Can an experiment be designed to prove or test motivation? Let’s say that a living cell has an agency, a robot simulates what a cell does, the result is an artificial cell that does the same things as the living cell. Is this cell alive, and does it have agency?

In these discussions several potential clashes come to the fore, which may be clashes only superficially. Natural vs artificial, biological vs technological, evolutionary vs computational. Much of the results of investigations are due to the perspective and interpretation of the scientist. Often common language is applied and twisted or perverted in order to emphasize the idea or result. Language becomes a tool, an obstacle, and a dogma. Therefore, it is through these interdisciplinary efforts that the benefits and limitations of language are quickly revealed. On the forefront of knowledge, the appropriate terms to even ask the proper questions may not exist. Constructing the linguistics of interdisciplinarity as in ABRA is a very helpful exercise for all participants who do not shy away from hard problems; problems which we acknowledge may have no quick nor clever resolution. Instead, time is needed to ponder the significance of the terms used in one’s mental gymnastics and in one’s discipline.

ABRA has thus become an experiment in pragmatics linguistic, since the construction of a common language is based not on dictionaries or encyclopedias, but on the pragmatic/intentional use of the terms that will constitute the basis of this interdisciplinary curriculum2. Key terms are being identified and put to debate in a discussion between perspectives that will ideally help teacher and students to look into reality from a manifold of perspectives of meaning. Our aim is not to abandon the specificity of our disciplines, but to enlarge our understanding of the world, to create new meaning and terms of interaction; in summary, to construct new fields or sub-fields of work and exploration.